Michigan's Onsite Shared Septic, Condominium Quandary

A commentary on Michigan homeowner's shared septic system troubles, trials, and rules.

Over the years, many of Michigan’s former single owner, cottage-style resorts (you know, the mini-“resort” with cabins on the lake rented by the week) were divided up and sold as condominiums. Unfortunately, the shared septic systems between condo units were generally not addressed during the condominium conversion. If unchecked, a condominium owner or association may be responsible for separating or upgrading shared septic systems after a condominium unit is purchased. This has caught numerous condominium owners by surprise when repair or replacement of the systems was required.

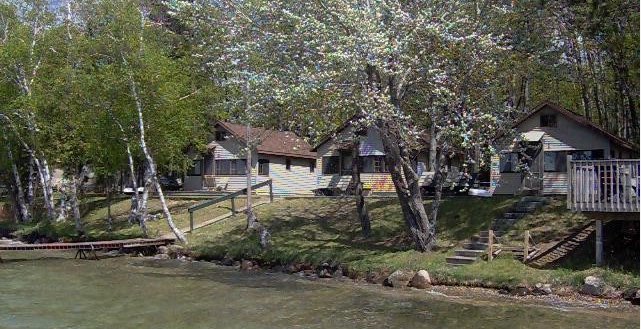

What if these cabins had shared septic systems?

What if these cabins had shared septic systems?In short, if your septic tank or drain field is behind someone else’s cabin, you and your neighbor could be in for costs no one planned. This is why:

What's a Shared Septic System?

A septic system used by two or more owners is considered by Michigan law to be a public system, even though a system may be privately owned. Public sewerage systems are governed by the Michigan Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (MNREPA, 1994 Public Act (PA) 451, as amended) in Part 22, Groundwater Protection; Part 31, Water Resources Protection; and Part 41, Sewerage Systems, the same rules that govern municipal sewage treatment works. These rules promulgated by the act were prepared and are administered by the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (MDEGLE). Conversely, individual septic systems are administered by local, county or district health departments. Because a two or more owner system is designated as a public system, the MDEGLE has jurisdiction unless the local health department has an agreement with the MDEGLE to administer public systems on its behalf.

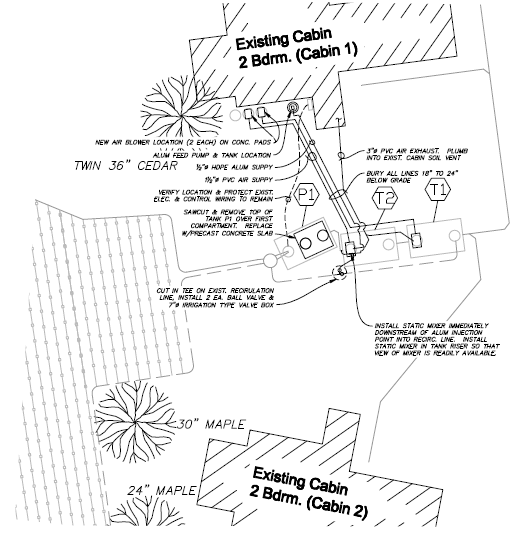

An example of an advanced, shared septic system

An example of an advanced, shared septic systemIf your shared septic system is working properly, even if it’s defined as a “public” system, you’re o.k. for now. To my knowledge, the MDEGLE has not required existing, shared systems to be replaced unless a system has failed, even though they are technically out of compliance with the Act. However, if a portion of a shared system is considered failed or needs to be replaced, the whole system must be upgraded to current rules. The average daily flow to the system determines which rules apply. (This is where its starts to get tricky, so if I lose you, you’re not alone. I’ll try to bring you back a little later.)

The Rules

In general, a Part 22 groundwater discharge permit is not required from the MDEGLE for sanitary sewerage systems if the average daily flow is less than 1,000 gallons per day (gpd) and the system meets the requirements of the local health department or the requirements described in the 1994 document “Michigan Criteria for Subsurface Sewage Disposal” (MCSSD) (Yes, its over 30 years old. Change at the speed of government...). These rules generally provide prerequisites of septic tank and drain field size. Single-family homes generally use between 100 and 300 gallons of water per day. If the flow is more than 1,000 gpd but less than 6,000 gpd, the system is generally still exempt from a Part 22 permit but must meet local health department requirements and meet the requirements of the MCSSD. These rules work where favorable soil and groundwater conditions exist. Many condominium sites near the water have high groundwater or poor soil conditions and are at odds with the above requirements.

These rules are better explained here.

Michigan's MCSSD document requires that there be a minimum of four feet between the bottom of a disposal system and the seasonal high groundwater elevation. If this does not exist at the site, there is an alternative in that the Benzie-Leelanau District and other Michigan District Health Department's sanitary code allows for disposal installation at less than four feet to groundwater if sewage is treated to a standard higher than required by the MCSSD, but unfortunately these local codes do not apply to condominium sites. That does not mean it can’t be done, it just means that the local health department has to get a sign-off from the State, and the State needs to accept the local health department’s advanced treatment criteria before they will acquiesce.

Further, many if not most of these converted resorts are considered "site" condominium developments, meaning the individual condominium units are the parcels of land and everything on or under them. Onsite sewage disposal at site condominium units, including shared septic systems, and any parcel of land that is smaller that one acre, are further regulated by the Land Division Act (1967 PA 288, as amended) via rules (Part 4) promulgated by the MDEQ and the Public Health Code Act (1978 PA 368). These rules require among other things, that septic systems are to be pre-approved prior to development of the condominium, but (more importantly in this discussion) allow that alternative methods of sewage treatment and disposal may be approved under certain circumstances.

(A Sir Walter Scott poem comes to mind, “Oh what a tangled web we weave…”)**

If you want to see the rules for themselves, or get a copy of the documents referenced here, go to the MDEQ Onsite Wastewater web page.

How to fix it

In summary, the following approvals are needed to install a privately-owned, public (in other words, a shared septic) sewerage system:

1. From the MDEGLE in Lansing, that an alternative sewage treatment and disposal system may be used on condominium sites (Part 4) so that;

2. From the local health department, may allow (per the Local Sanitary Code) the use of advanced treatment measures so that;

3. From the local MDEGLE and Lansing offices, that they may waive the four-feet-to-groundwater rule (per Part 22) and agree to advanced treatment so that;

4. From the local MDEGLE office, that you may submit a design for and receive a permit (per Part 41) to install.

As you can see, the multiple rules and agencies, and agents within agencies, enforcing the rules regulating sewage disposal have created somewhat of a round-robin approach (I leave the word “quagmire” and other more colorful slogans to private conversations) to getting a system approved and installed pretty difficult and time-consuming for the lay person. Here’s how you can avoid the trouble:

Buyer Beware...

Before you put your down payment on that cabin or cottage, be sure to ask the current owner about the septic system and where it is. A receipt for a recently pumped septic tank is not enough. Many townships and municipalities have passed point-of-sale septic system inspections, but the inspection itself is generally related to the health of the septic field and condition of the tank, not ownership or number of users. Your best bet is to contact your local health department and ask them about the development and unit you’re considering (have the parcel number handy). Get a copy of the original septic permit and ask them to explain it to you. They will likely have the information you need to determine if your future home-away-from-home has its own septic system, is shared or is part of a larger system, its age, and its status.

Would you buy a cottage if it had a shared septic system?

Would you buy a cottage if it had a shared septic system?Image from visitlakegeorge.com

... But Enjoy Yourself

If you have already committed to your dream spot, don’t worry. It’s not the end of the world; it’s just the septic system. If you have a good, working individual septic system, go put the little umbrella in your drink and sit and watch the waves (or whatever your fancy). As I said before, if you’re in a public (or shared septic) system and the system is working well, Big Brother shouldn’t be knocking on your door anytime soon (unless, of course, things change... ). You and your condominium neighbors should, however, acknowledge the fact, plan for costs of maintenance and/or upgrade, and create a reserve fund for when that time comes. It’ll benefit you in the long run and help to keep your resale value up as more and more purchasers follow the advice in the paragraph above.

I would rather expend a small amount of time to help a condominium association with shared septic systems plan for future costs than take a call from one that says in effect, “Houston, we have a problem…”

**The rest of the line in Sir Walter Scott’s poem, “ …when we first practice to deceive”, is not, I hope, what our dear legislature had in mind when these rules were developed (I know that the rules were developed over many years and legislative sessions by different elected officials in office at different times).

We Can Help

For owners of systems that are

failing or have had issues with the State or their local health department, there is no

magic bullet and some costs may have to be expended. The good news is that the performance of

small wastewater treatment systems has gone up significantly, allowing an

alternative to standard septic systems or (gulp!) holding tanks. If you are

one in this situation, contact Prince-Lund Engineering, PLC and we'll let you know if we can help.

For More Information

Send Prince-Lund Engineering, PLC a message with questions or comments on this topic (This link takes you to the email contact form). We’re inclusive, not exclusive. That means engineering is discussed in a way that’s easy, understandable, and productive. You’ll enjoy what you can build with Prince-Lund.

<- Return from Shared Septic back to Wastewater Treatment Design

<- Return to Prince-Lund Engineering, PLC Home Page

Prince-Lund Engineering

Quick Contacts

Email:

Go to the Contact Form to email directly.

Looking for Design Software? Try FRPpro™ free!

New! Comments

Please Ask Questions! Your Opinion Counts!